Practice Note on Beliefs and Biases

Messages we receive

We all have beliefs and biases

Having beliefs and biases are a part of being human. What an individual learns about the world and how society is structured and functions is formed by the early and consistent messages received from family, peers, educators, mentors and a wide range of media sources.

But often, in both obvious and subtle ways, society conveys inaccurate messages. Among other things, these messages stem from longstanding beliefs and views about:

-

-

who and what is valued in society;

-

who is capable and who needs help; and,

-

the ways peoples and groups are supposed to function.

-

These dominant messages strongly influence the ways people behave and the beliefs they establish, nurture and safeguard.

This is confirmation bias; a type of cognitive bias that involves favouring information, people or groups that confirm an individual’s existing beliefs or biases while ignoring or failing to seek information that could counteract or disrupt those existing beliefs.

This occurs when individuals actively seek ‘evidence’ or favour information that confirms their existing beliefs while ignoring or failing to seek information that could counteract or disrupt those existing beliefs.

Note how often, and in what ways, messages about what is viewed as acceptable, common and appropriate in society surface in:

-

- the media;

- conversations with family and peers;

- exchanges with colleagues, families and children; and,

- policies and practices in your workplace.

Dominant messages infiltrate our day-to-day experiences which make them very powerful. They can be harmful in general, but may be more harmful when they go unnoticed. Bringing them to light and critically reflecting upon them can support change and growth.

Below are some examples of powerful messages that are often conveyed in subtle ways. Review the list and consider other biased messages you may encounter. Share your observations with your colleagues and consider the impact of these assumptions on your professional practice and the people in your learning environment:

| • Marriage is a union between a man and woman • If women have children, they are married • Christmas is the most significant holiday • Children don’t see race • Being thin is healthy • Families have access to transportation • All children have opportunities for play |

• Drinking water is safe everywhere • Gender is revealed at birth, • All people can walk • All families travel on summer holidays • People who speak with accents aren’t from Canada • Canadians are not racist |

Consider whether any of society’s powerful messages may be influencing your beliefs or biases and, as a result, have the potential to harm a child, family or colleague. In certain instances, identifying some of your conscious beliefs may seem relatively easy but reflecting on these conscious beliefs can assist you in becoming aware of your unconscious beliefs, too.

While it’s important to look at your conscious beliefs and biases, it is perhaps even more vital to dig deeper and become aware of your unconscious beliefs and biases. Everyone has them and, as the term suggests, these beliefs and biases are potentially harmful because they are less obvious or not obvious at all.

Click here for an example related to the practice of early childhood education

As an RECE, your education exposed you to information, research and practical experiences that highlighted the value of play-based learning and care. You established, and continue to nurture, this belief through continuous professional learning centred on the value of inquiry and play. Your pedagogical practice and inclusive curriculum design is influenced by your beliefs about the value of play.

During conversations with families, you articulate these beliefs and encourage them to play with their children. You assume they will share your passion and beliefs and, therefore, will make time for play.

Some families share positive stories with you about their experiences with inquiry and play, which further confirm your beliefs about its value. Because the family made time for play, you may also assume that they care deeply about their children.

In contrast, some of the other families either do not share their experiences or they express frustration with play. You strongly believe in the value of this learning activity and believe that families who play with their children truly care. Therefore, you may be at risk of making assumptions that families don’t care if they:

-

-

- don’t play;

- don’t try to understand the importance play;

- don’t play in a way that you believe in; or,

- don’t talk about play.

-

Your beliefs about the value of play and each family’s approach to play lead to assumptions that generate biases about specific children and their families. These biases can unconsciously, or consciously, affect the way you interact with them.

In the example above, the RECE is conscious of their beliefs about play. These conscious beliefs and biases influence the RECE’s assumptions about the families and their varying responses to play. But the RECE’s practice is also influenced by beliefs they may not be aware of. These unconscious beliefs and biases can further influence the RECE’s practice. It is clear that a deeper investigation is needed to uncover them.

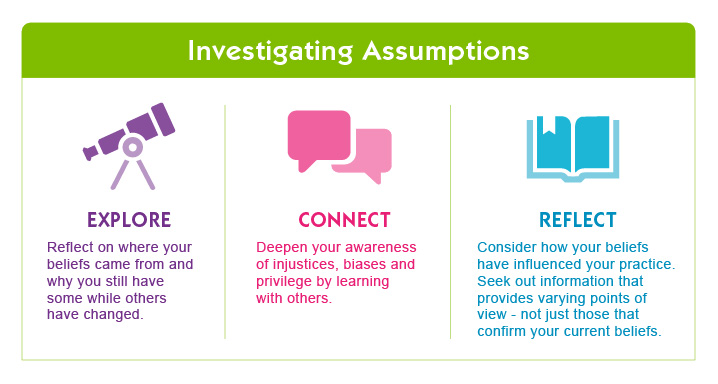

Remember that everyone has beliefs and biases that impact their decisions and behaviours. As you consider your beliefs, assumptions and biases, the next section can serve to guide you in the process of becoming more aware. These questions may be challenging, but by reflecting on them and taking action to positively influence your practice, they can prevent potential harm to children, families and/or colleagues.